12 ancient sites to go in western Iran

TEHRAN – From the coasts of the Persian Gulf to the lush mountainous forests of the northwest, and from snow-tipped northern cliffs to scorching southern deserts, here is a pick of ancient sites to inspire, delight and motivate if willing to visit wild western Iran.

It’s a time to leave the bright lights and tourist delights of Isfahan, Yazd, Shiraz, and Tehran getting off the beaten path to track down astonishing millennia-old relics among the dusty wilds of ancient Persia.

Ready to explore? What awaits you is traversing through eroded volcanic plateaus, passing under the mournful gaze of long-abandoned castles and exploring ancient river valleys, and places of worship.

Bisotun

Bisotun bas-relief bears exceptional testimony to the distinctive visual arts in prehistoric Iran. It is nested on an elevated limestone cliff of a mountain of the same name in the western Kermanshah province.

Inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage site, the inscription is a patchwork of immense yet impressive life-size carvings depicting the king Darius I and several other figures. It was the first cuneiform writing that was deciphered in the 19th century.

The inscription, measuring about 15 meters high and 25 meters wide, was created on the order of Darius I, byname Darius the Great (r. 522–486 BC). It bears three different cuneiform script languages: Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian.

UNESCO has it that Bisotun bears an outstanding testimony to the important interchange of human values on the development of monumental art and writing, reflecting ancient traditions in monumental bas-reliefs.

Armenian churches

To the untrained eye, Iran’s earliest churches may seem modest structures to some but they bear testimony to a vast panorama of architectural and decorative scenes associated with Armenian culture blended with other regional cultures: Byzantine, Orthodox, Assyrian, Persian and Muslim.

St. Thaddeus, St. Stepanos and the Chapel of Dzordzor are three photogenic ancient churches that constitute the Armenian Monastic Ensembles of Iran, which were collectively inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage in 2008. They are dotted in fresh and green lands of northwest Iran and are important pilgrimage sites for Armenian-Iranians and others from across the globe.

Also known as the Qareh Klise (“the Black Church”), St. Thaddeus, as one of the oldest surviving Christian monuments in the country, is situated in Chaldoran county some 20 kilometers form Maku, adjacent to the borders of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkey.

The ancient Church shows off elaborate bas-reliefs of flowers, animals and human figures on its façade and exterior walls. It bears verses of Old and New Testament in Armenian calligraphy as well.

The Chapel of Dzordzor stands tall on the outskirts of Maku. The name narratively originates from a famous painter Hovans Yerz, known as Dzordzortzi, who supervised the chapel’s restoration for a while.

Aras River Valley

Forming Iran’s northern border with Azerbaijan and Armenia, which are still technically in conflict over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh, the scenically imposing Aras River Valley has played host to traders, spies and marauding armies since biblical times, According to Lonely Planet.

Safe inside a line of watchtowers, the road along the dramatic southern Iranian bank meanders spectacularly through mudbrick villages, crumbling ruins and soaring jagged peaks. Whether the Aras is actually the River Gihon from the Garden of Eden is debatable, but it’s obvious that the northern bank, with its bombed-out stations, abandoned trains and barricaded tunnels, is no paradise.

Highlights of the valley include the Kordasht Hammam, an ancient subterranean bathhouse within bubble-blowing distance of Armenia, and the Khodaafarin Bridges, dating from the 13th century, still spanning the Aras, now to a post-apocalyptic no-man’s land. While travelling through the valley on the Iranian side is perfectly safe, be careful where you point your camera, as the border guards are notoriously paranoid.

Tabriz Bazaar

Possibly the easiest ancient site to find in western Iran is the sprawling, still-open-for-business Tabriz Bazaar, one of the largest and oldest covered bazaars in the world.

It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2010 and was mentioned by Marco Polo when he travelled the Silk Road in the Middle Ages. A labyrinth of interconnected covered passages that stretches for about 5 km, the bazaar has been a melting pot of cultural exchange since antiquity.

It embraces countless shops, over 20 caravanserais and inns, some 20 vast domed halls, bathhouses, and mosques, as well as other brick structures and enclosed spaces for different functions. Its history dates back to over a millennium, however, majority of fine brick vaults that capture most visitor’s eyes date from the 15th century.

Takht-e Soleiman

Situated in the southeastern highlands of West Azarbaijan province, Takht-e Soleiman encompasses a lake roughly 80 by 120 meters and a Sassanid-era Zoroastrian temple complex dedicated to Anahita, an ancient goddess of fertility, parts of which were rebuilt in the 13th century during the Ilkhanid era.

The ensemble was established in a geologically anomalous location as the base of the temple complex sits on an oval mound roughly 350 by 550 meters. It draws local and foreign travelers who want even for minuets revel in its peaceful atmosphere.

According to Britannica Encyclopedia, its surrounding landscape was probably first inhabited sometime in the 1st millennium BC. Some construction on the mound itself dates from the early Achaemenian dynasty (559–330 BC), and there are traces of settlement activity from the Parthian period.

Sheikh Safi-al-Din Mausoleum

Behind high walls on Ardabil’s main drag lies one of Sufism’s most revered fathers, Sheikh Safi. Originally constructed after his death in 1334 by his son Sadr, the shrine was expanded by the eponymous Safavids in the 16th century.

UNESCO has recognized the intricate blue mosaics and interior vaulted ceilings, tiled courtyards, formal gardens, kitchens, hammams and myriad support buildings as a pre-eminent example of traditional Iranian architecture. Several museums round out the site, and restoration work continues while Sufi pilgrims, students of Islamic art and curious tourists mingle. It's a pity most of the famed pottery collection is now in St Petersburg.

Qal’eh Rudkhan

Near the much-photographed village of Masuleh, Rudkhan Castle is a fine example of a Seljuk-era fortress, clinging to a wooded spur of the Alborz Mountains. Originally a Sassanid (pre-Islam Persians) structure, the wily Seljuks (medieval Turks) arrived 800 years later and account for the current gnarly bastion, where 1500m of stone-thick walls, interspersed with archers’ slit windows and drop-holes for boiling oil, link the numerous unassailable towers.

This brutal stronghold is reached by a ridiculously steep (though thankfully shaded) climb. Well-worn stone steps wind high above a moss-fringed stream through lush forests to the daunting entrance gate. Catch your breath by pausing for a shared chay (tea) with the notoriously friendly locals.

Susa

Now sprawling in the southwest of modern Iran, Susa is one of the oldest yet magnificent cities in the world. No need to head out of town, the modern oasis of Shush sprawls around the base of ancient Susa, whose relics occupy the flat-topped central hill.

A UNESCO World Heritage, Susa was once the capital of the Elamite Empire and later an administrative capital of the Achaemenian king Darius I and his successors from 522 BC.

Excavations have uncovered evidence of continual habitation dating back since about 5000 BC. The earliest urban structures there date around 4000 BC.

Part of Susa is still inhabited as Shush, Khuzestan province on a strip of land between the rivers Shaour (a tributary of the Karkheh) and Dez.

According to UNESCO, “the excavated architectural monuments include administrative, residential, and palatial structures” and the site contains several layers of urban settlement dating from the 5th millennium BC through the 13th century CE.

Relics unearthed from the region demonstrates that even the earliest potteries and ceramics in Susa were of unsurpassed quality, decorated with birds, mountain goats, and other animals designs.

Qal’eh Babak

Babak Khorramdin, Azeri nationalist and local bad-boy, perched his magnificent 9th-century citadel on a rocky precipice in the mountainous far north, high above the town of Kaleybar.

These days, Babak Castle can be reached by several hours of stiff climbing from the village below. The final approach on a stone staircase winding through a rock-cleft above sheer cliffs is pure Tolkien. The resulting 360-degree views are appropriately stunning, and the castle looks particularly photogenic in the low light between late autumn and early spring. Give it a miss in summer as there’s no shade on the entire climb.

Shushtar Hydraulic System

Known as a ‘masterpiece of creative genius’, the Shushtar Historical Hydraulic System comprises bridges, weirs, tunnels, canals and a series of ancient watermills powered by human-made waterfalls in southwest Iran.

It is named after an ancient city of the same name with its history dating back to the time of Darius the Great, the Achaemenid king.

Inscribed on UNESCO World Heritage list in 2009, the Shushtar Historical Hydraulic System may testify to the heritage and the synthesis of earlier Elamite and Mesopotamian knowhow. According to UNESCO, the ensemble was probably influenced by the Petra dam and tunnel and by Roman civil engineering.

These days some of the bridges have collapsed, but the water rushing through the mill tunnels and tumbling out into the holding canal is still an impressive sight.

Oljaytu Mausoleum

A UNESCO World Heritage site, the 14th-century Mausoleum of Oljaytu is highly recognized as an architectural masterpiece particularly due to its innovative double-shelled dome and elaborate interior decoration.

The very imposing dome stands about 50 meters tall from its base. Covered with turquoise-blue faience tiles, the stunning structure dominates the skyline of Soltaniyeh, an ancient city in Zanjan province, north-western Iran.

The interior has long been under renovation, chockfull of scaffolding poles. However, its decoration is such impressive that scholars including A.U. Pope described it as ‘anticipating the Taj Mahal’. It is the earliest existing example of the double-shelled dome in Iran.

A great-grandson of Hulegu, founder of the Il-Khanid dynasty, Oljaytu was a Mongol ruler who, after dabbling in various religions, adopted the Shia name Mohammed Khodabandeh.

The city of Soltaniyeh was briefly the capital of Persia’s Ilkhanid dynasty (a branch of the Mongol dynasty) during the 14th century.

According to the UNESCO, the Mausoleum of Oljaytu is an essential link and key monument in the development of Islamic architecture in central and western Asia. Here, the Ilkhanids further developed ideas that had been advanced during the classical Seljuk phase (11th to early 13th centuries), during which the arts of Iran gained distinction in the Islamic world, thereby setting the stage for the Timurid period (late 14th to 15th centuries), one of the most brilliant periods in Islamic art.

The very large dome is the earliest extant example of its type, and became an important reference for the later development of the Islamic dome. Similarly, the extremely rich interior of the mausoleum, which includes glazed tiles, brickwork, marquetry or designs in inlaid materials, stucco, and frescoes, illustrates an important movement towards more elaborate materials and themes.

Tchogha Zanbil

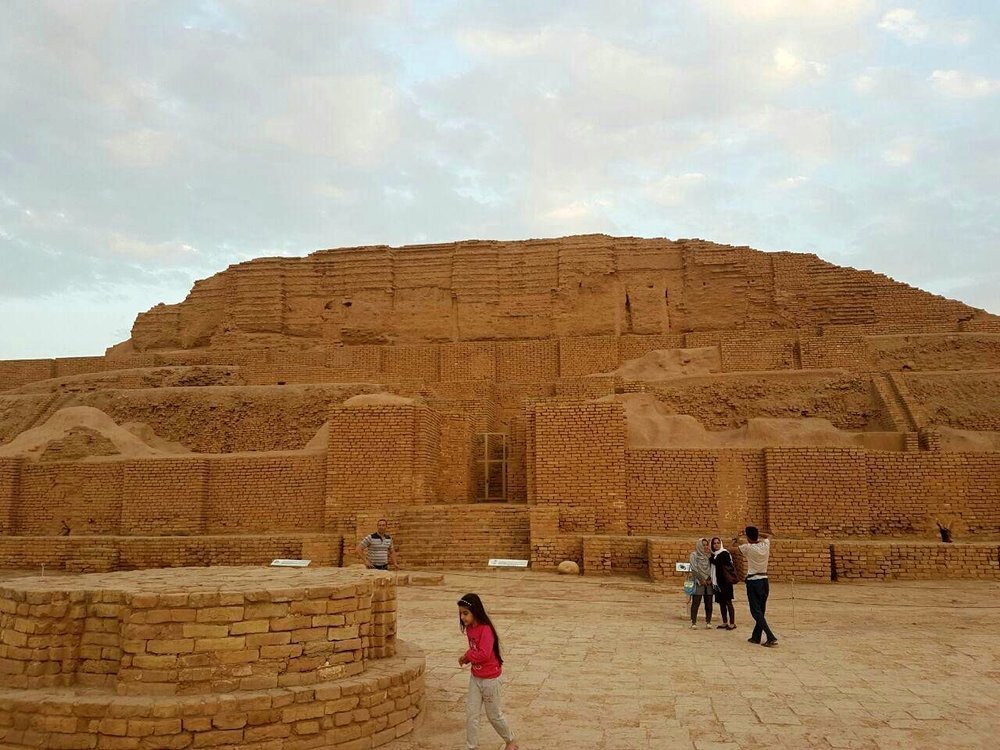

A topmost tourist destination in Khuzestan province, the magnificent ruins of Tchogha Zanbil is considered by many the finest surviving example of the Elamite architecture in the globe.

The brick ziggurat was made a UNESCO site in 1979. It is a multi-levelled square structure in which each level diminishes in size as it reaches for the sky, like a tiered wedding cake.

People visit the UNESCO-registered Tchogha Zanbil in southwest Iran. The ziggurat overlooks the ancient city of Susa (near modern Shush) in Khuzestan province.

Its construction started in c. 1250 BC upon the order of the Elamite king Untash-Napirisha (1275-1240 BC) as the religious center of Elam dedicated to the Elamite divinities Inshushinak and Napirisha.

The prehistoric mud-brick complex bears testimony to the unique expression of the culture, beliefs, rituals and traditions of one of the oldest indigenous communities of Iran.

The ziggurat overlooks the ancient city of Susa (near modern Shush) in Khuzestan Province. Reaching a total height of some 25m, the ziggurat was used to be surmounted by a temple and estimated to hit 52m during its heyday.

UNESCO says that Tchogha Zanbil is the largest ziggurat outside of Mesopotamia and the best preserved of this type of stepped pyramidal monument.

Tchogha Zanbil was excavated in six seasons between 1951 and 1961 by Roman Ghirshman, a Russian-born French archeologist who specialized in ancient Iran.

AFM/MG

Leave a Comment